I'm afraid a man who says something like that about how the world looks (Our Mister Brooks) is a man with a jaundiced eye and possibly worse afflictions. Liverish. Sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, but not thought at a very high level.

|

| Portrait of Alan Simpson, with Erskine Bowles as a boil erupting from the Senator's shoulder. By Donkey Hotey, 2011. |

Here's a Shorter Brooks for today (two for the price of one!):

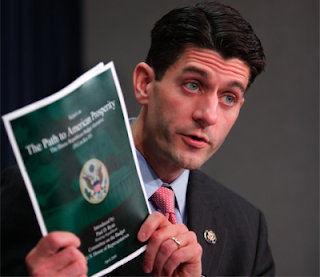

1. I pick Paul Ryan because he knows that rising Medicare costs are the most scariest urgent problem facing our country!

2. But that is like so last Tuesday! Medicare, Medicare, Medicare, it's all he ever thinks about! Get a grip, Congressman, and do your duty!

All because—apparently Brooks just heard about it for the first time—Ryan refused to sign off on the Bowles-Simpson plan for deficit reduction (which Brooks insists on calling "debt reduction") in 2010, and refused precisely because it failed to do anything about rising Medicare costs, thereby showing his willingness to

sacrifice the good for the sake of the ultimate....

Paul Ryan has a great campaign consciousness, and, when it comes to things like Medicare reform, I agree with him. But when he voted no on the Simpson-Bowles plan he missed the chance to show that he also has a governing consciousness. He missed the chance to do something good for the country, even if it wasn’t the best he or I would wish for.

There's something about the

Bowles-Simpson Commission, by the way, that hardly anybody left or right has seemed to understand very clearly: it was certain to fail from the outset, as certain as if the president had planned it that way. If the president did plan it that way, I would not be in the least shocked; indeed, I kind of hope he did, since that would tend to suggest that he knows what he's doing.

Because if a great part of the Science of Government (if not absolutely the whole, as

Dickens had it) consists of the art of perceiving HOW NOT TO DO IT, then the bipartisan commission, with its distinguished members chosen from inside and outside the legislature, and its solemn mandate, is the very archetype of the vehicle through which it is not done.

What even Dickens did not understand is that sometimes not doing it is really much the best plan. Thus in 2010, when the great cry came up from the bobbleheads across the land to do something about the deficit ("Mr. President, tear down this deficit!"), actually doing it would have seriously harmed our already badly wounded economy; but not doing it became extremely difficult as the legislators and eventually even the print press began taking up the cry.

I don't want to get into whether President Obama could or could not at this point have said, "No, actually Dr. Krugman is right about this one, we need a

bigger deficit just now." He certainly had realized that Republicans in Congress wouldn't vote for anything with his name on it unless they were tricked into it in some extremely subtle way. He seems to have felt up against one of those

Tough Decisions, which means a bad decision taken when you didn't want to think about a good one.

So the president set up his best defense: not just a bipartisan commission, but a bipartisan commission endowed with special powers. It had a blank check, as it were, endorsed by Congress, which agreed that any plan coming out of the commission should be regarded as law, as if the Congress had already specifically voted for it.

This provided what you could call an extra degree of fail-safe, in that in the unlikely event that Bowles-Simpson really did come up with the plan, Congress could immediately begin on the process of denying that that was what they had meant at all, and starting all over again. *

In the end this was not necessary, as Bowles-Simpson were able to tie themselves into knots without any outside help, thanks partly to Representative Ryan, and no proposal ever emerged from the committee's stringent rules, although one of them did get publicized a great deal. Instead we are now living with a different case of tricking Congress into voting for something it absolutely does not want, the famed "

fiscal cliff" which is somehow going to have to be bridged by the lame ducks after the election.

I do wish my emoprog colleagues would stop referring to the Bowles-Simpson "plan" as representing what what that crypto–Gold Bug Barack Obama really wants, though. I'm sure he thinks the deficit ought to be tightened up, just as soon as everybody has lots of money and the tax receipts start rolling in, but not before then, and not with such a nasty instrument.

By the same token, I wish the Central Committee of the Panditry would ban their members from using it as the symbol of some kind of lost centrist paradise where for one brief shining moment everybody agreed to sacrifice themselves to a vision of the world as Tom Friedman wants it to be. It's just a piece of used ordnance in the war of How Not to Do It, that has served its embarrassing purpose and can now be forgotten.

For that matter, so is Paul Ryan. He's the vice presidential candidate, for Pete's sake! He used to be philosophically useful to the panditry as an example of how Republicans Have Intellectuals Too. He used big words and never got cranky if your attention kind of drifted away, and he had his famous budgets, these beautifully bound little pamphlets—say, what do you suppose was

in those things?**

*Can God make a stone so big She can't roll it? Good question. Can Congress create a trigger so ineluctable they can't wriggle their way out from in front of it? No. **Tthe House Budget Committee website offers richly produced propaganda for them, in written and video forms. Wikipedia's article on The Path to Prosperity links to PDFs of two of the pamphlets, which are more in your PowerPoint format, with substantial sections of ordinary prose. To Brooks, the old symbolic Ryan was something you could really chew on as you thought about your next column, having so many little affinities with yourself, also a more or less clubbable Republican intellectual, and then because his subject was budgetry—eew!—you wouldn't go so far as to find out what he actually thought about anything. Math is for kids who go to public school. But now that he's descended into the fray of the presidential campaign, Brooks must look at any rate at his biography, and is inevitably somewhat shocked, shocked to find that there is negativity—negativity!—in this nominee. Poor Brooksie, you've got a lot of surprises coming in the next few months.

.jpg)